The Teaching Practice and Research Loop: creating better learning experiences and outcomes

Francis Ben

Director, Postgraduate Programs and Research

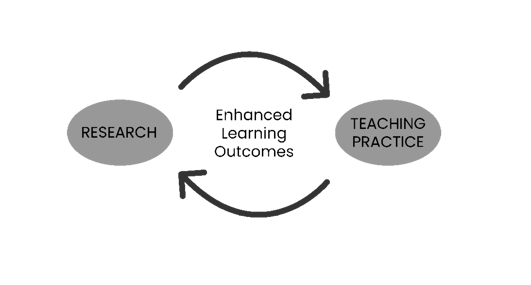

The ‘research – teaching practice loop’ (Figure 1) is a simple diagram but forms the basis for enhanced educational practices to produce better learning experiences and outcomes. This article shows ways in which schoolteachers can easily engage in research, particularly action research, to inform their practice, and to also contribute to the knowledge of the wider Education community. Tabor can assist teachers with data gathering and analysis, and application and publication of their research.

Figure 1. The research - teaching practice loop

Why is research needed?Research studies of the philosophies behind great educational thinkers such as Piaget, Dewey, Vygotsky, and Freire have explored and evaluated the base philosophical ideas of their pedagogy theories. As a result, we now have much better understanding of base learning theories such as constructivism, inquiry-based learning, discovery learning, experiential learning, cooperative learning, differentiated teaching approaches, and critical pedagogies.

Contemporary research continues to explore, for example, the intricacies of the constructivist theory of learning. Recent explorations include that of Guthrie and McCracken (2010) who studied Reflective Pedagogy and how it is implemented in online learning environments – critically useful in current times where education systems across the world deal with a pandemic that disrupted traditional (face-to-face) delivery of curricula. More recent examples of research-based pedagogies (so called ‘Innovative Pedagogies of the Future’) that have emerged from a better understanding of the science of learning have been developed and evaluated by Herodotou et al. (2019). These include formative analytics, teachback, place-based learning, learning with drones, learning with robots, and citizen inquiry.

Teachers as Researchers

Thankfully, research into teaching practice is not exclusive to Education ‘experts’ or university academics. Teachers in schools are in a perfect position to engage in real-life research as they practice teaching most days of their work year. A common hurdle to research is of course the daily workload demands (teaching, and extra-curricular activities). There is also a common perception that conducting research is so time consuming on top of the usual teaching demands, that simply thinking about it is off-putting. That may be true for traditional (formal) research. However, teachers can engage in a form of research which aligns more directly with their practice, and therefore can be conducted at the same time as their teaching practice. Action Research consists of four main stages of an on-going cyclic process: reflect – plan – act – observe (McNiff & Whitehead, 2011).

Researching Real Practices

Action Research focuses on immediate application (practice) and not on the development of theory (Abdullayeva et al., 2019). Action research can be undertaken by teachers individually or in small groups. Think of it as research done by teachers for themselves (Mertler, 2014). Broad areas in education where action research may be undertaken include teaching practices (methodologies), curriculum development, and educational leadership. More specific areas of action research could include literacy & numeracy learning, wellbeing, investigation of creativity or differentiation, and evaluating strategies for engagement in learning (managing student behaviours).

Citing a range of educational research papers on action research, Hine and Lavery (2014) outline the following benefits of Education-based Action Research:

- It can be used to fill the gap between theory and practice.

- It helps teachers to develop new knowledge directly related to their classrooms.

- It facilitates teacher empowerment when they are allowed to collect their own data to use in making decisions about their school and classroom.

- It is an effective and worthwhile means of professional growth and development.

Hine and Lavery note that action research provides teachers with the technical skills and specialised knowledge to be transformative within their professional domain, thus allowing them to be innovative in their professional lives.

Action research does NOT require extensive training and is akin to the thinking processes of any teacher. Having both a broad and in-depth knowledge and understanding of the processes of research would of course be advantageous to enhance teachers’ problem-solving capabilities. But doing action research enhances teachers’ reflexive skills and research understandings. For example, a teacher who undertakes action research that focuses on enhancing the relational aspects of learning online (one of the major challenges faced during the COVID-19 pandemic) could utilise data to quickly identify strategies that worked most effectively and thus modify their practice, and through the action research process the teacher is also learning more about and practicing research skills.

Developing Research Skills

Teachers wanting to get involved in action research or who are already involved in research-led teaching can further develop their research skills. Tabor’s postgraduate Master of Education and the Master of Leadership programs include significant research knowledge and skills development components.

These postgraduate programs in Education include action research as a core element as it holds significant value to improving practice within classrooms, in schools, and the broader community (Hine, 2013). As lifelong learners committed to continuing development and improvement of the quality of education learners receive, teachers are increasingly expected to combine teaching and researching skills, not only to cope with the changing demands of education, but also to contribute to the dynamic knowledge about ways that learning could positively contribute to society.

Teachers, educators and leaders are warmly invited to partner with Tabor to develop their educational or leadership qualifications, to learn more about traditional and action research, or to collaborate in undertaking classroom-based action research.

See the full Thinker Magazine here

References

Abdullayeva, M. M., Arifjanova, N. M., Mingniyozova, Z. A., & Turayeva, D. I. (2019). The difference of action research with traditional research and the role of action research in teaching FL. European Journal of Research and Reflection in Educational Sciences, 7(12), 145-149.

Guthrie, K. L. & McCracken, H. (2010). Reflective pedagogy: Making meaning in experiential based online courses. The Journal of Educators Online, 7(2), 1-21.

Hine, G. (2013). The importance of action research in teacher education programs. Issues in Educational Research, 23(2), 151-163.

Hine, G., & Lavery, S. D. (2014). The importance of action research in teacher education programs: Three testimonies. Teaching and Learning Forum 2014: Transformative, Innovative and Engaging. Retrieved from https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1076&context=edu_conference

Herodotou, C., Sharples, M., Gaved, M., Kukulska-Hulme, A., Rienties, B., Scanlon, E., & Whitelock, D. (2019). Innovative pedagogies of the future: an evidence-based selection. Frontiers in Education, 4(113). doi: 10.3389/feduc.2019.00113

McNiff, J. & Whitehead, J. (2011). All you need to know about action research (2nd ed.). SAGE.

Mertler, C.A. (2014). Action research: Improving schools and empowering educators (4th ed.). SAGE.